1MG FlippingBooks

INCENTIVISING

Alan Garcia

For firms investing in R&D, Alan Garcia believes one policy tool has an outsized – and measurable – impact.

Globally, governments provide programs to support business investment in R&D. For the past 35 years, R&D tax incentives have provided Australia-based businesses with financial support to develop new and/or improved products, processes, services, devices and materials.

A country’s R&D policy settings must align with its broader strategic economic objectives, including productivity and other growth drivers. Productivity is often defined as the ratio of a volume of output and a volume of inputs. It measures how efficiently production inputs (such as capital and labour) are used to produce a certain level of output.

It follows that Australia’s ability to improve its standard of living depends, in large part, on its ability to increase output per worker. In addition to demographic changes and labour force participation, productivity is a key determinant of long-term economic growth.

Australia’s productivity is going backwards

Empirical evidence indicates that higher productivity is tightly linked to higher wages. Unfortunately, the 2020 Productivity Commission report Can Australia Be a Productivity Leader? showed that labour productivity fell in Australia for the first time since 1994, by 0.2 per cent.

Australia lags behind the United States, France and Germany, ranking sixteenth in productivity among OECD member nations, despite ranking fifth in number of hours worked per person. An average worker in the US can produce in four days what it takes an Australian worker five days to produce. Australian workers produce less per hour than German and French workers.

The challenges for Australia are our land mass, low population density and remoteness, and the effects that these have on efficiencies of scale vis-a-vis production/manufacturing and distribution channels. These are factors that undoubtedly influence our productivity results.

It is important to note that approximately 80 per cent of Australian employment relates to the services industry. Therefore, increasing productivity in that field to drive economic growth must be an immediate focus for policymakers.

Stability and predictability needed

Industry investment, particularly as it relates to services and technology, is a strong enabler of productivity growth. But businesses that invest in R&D require stability and predictability to plan their R&D investment in the face of global economic volatility, particularly in light of the post-COVID-19 economic conditions.

Research has shown that the beneficial effects of R&D tax incentives are greatly reduced when those incentives are modified frequently. By creating a stable program and committing to an internationally competitive R&D tax incentive, Australia will be able to attract investment and retain positive “spill-over” effects that will promote productivity and economic growth in the long term. Frequent changes and reductions to R&D tax incentives reduce efficacy and lead many companies to consider either locating their R&D programs elsewhere and/or reducing their operations locally. Proposed changes to Australia’s Research and Development Tax Incentive (RDTI) saw a corresponding drop in Australia’s business expenditure on R&D as a percentage of GDP, from 1.0 per cent of GDP in 2015–16 to 0.9 per cent of GDP in 2017–18.

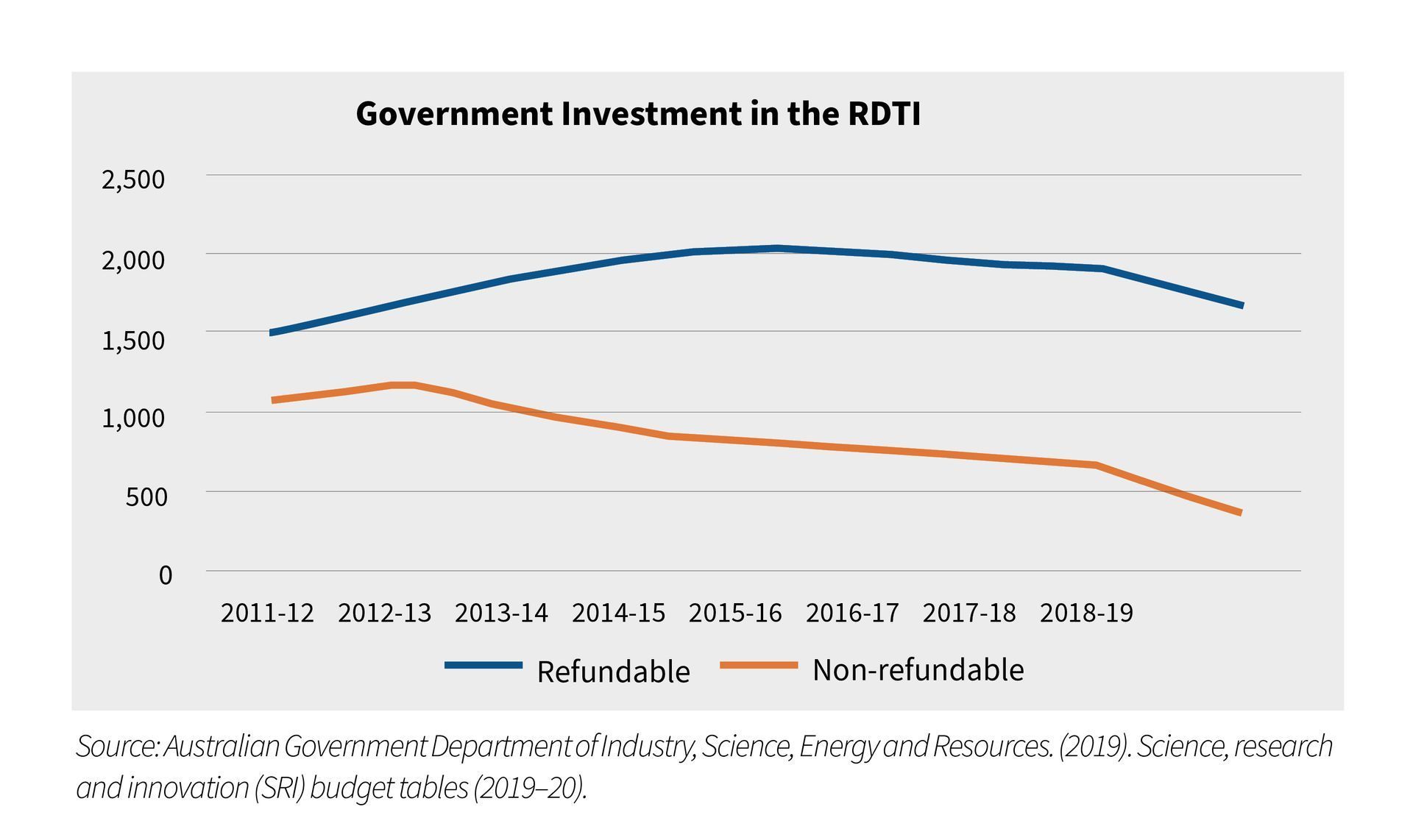

R&D tax incentives should be designed to meet the needs of large corporations and young, knowledge-based firms while protecting local resources and intellectual property from inappropriate cross-border planning. Recent interpretations by regulators of eligible R&D activity and associated expenditure have caused an element of uncertainty across the business community, particularly with respect to software - and technology-related R&D claims. Arguably, this has contributed to a drop in R&D expenditure, as shown in the following graph. A combination of legislated reductions to the benefit, business’ lack of confidence in the program and more attractive programs offshore have all had an influence.

Best practice in Europe

A 2014 EU report put forward principles of best practice for R&D tax incentives, grouped into three categories: scope, target and practice. According to the report, tax incentives should, inter alia:

- target expenditure that has strong knowledge-related flow-on effects – research has shown that larger firms contribute more to spill-over effects be volume-based (such as Australia’s RDTI) rather than incremental, as volume-based regimes are more readily understood and applied, do not distort investment planning and incentivise R&D expenditure at all levels

- provide a carry-over facility to enable firms to receive the benefit even when they are not yet profitable (such as cash refunds, as per Australia’s RDTI)

- target younger and smaller firms – Australia’s RDTI provides a relatively generous benefit to companies with a turnover under $20 million, and this is one of the strengths of the existing program

- conduct systematic evaluations (according to international standards) to ensure the efficacy of the regime.

Both global and local research supports the contention that R&D tax incentives improve productivity, generate important spill-overs, and support STEM employment and wage growth. There is, however, a tension between the attempts of governments to reduce taxes foregone as a consequence of R&D tax incentives and the need to acknowledge the critical short-, medium- and long-term benefits that such incentives provide.

If R&D tax benefits are reduced or restricted, it is considered that companies may reduce their existing baseline R&D expenditure in Australia (by reducing product and process R&D), defer higher-risk R&D and/or undertake R&D elsewhere.

Alan Garcia was the Asia Pacific Regional R&D Partner for KPMG, between 2000 and 2020