1MG FlippingBooks

ZAHA HADID: THE GREATEST ARCHITECT OF THE 21ST CENTURY?

Monique Ross

In the realm of architecture, there are those who merely shape spaces, and then there are those who redefine the boundaries of what we consider possible. With her fluid, dynamic designs, acclaimed Iraqi-British architect Zaha Hadid (1950-2016) no doubt falls into the latter category.

Zaha Hadid was born into a city of juxtapositions. Baghdad was a bustling metropolis where tradition and progress were colliding; ancient buildings stood side-by-side with modern developments. Her father, a wealthy industrialist and politician, took the young Hadid on walks through the city, and on visits to the Sumerian cities in the south of Iraq. He was a great storyteller, and these journeys provided fertile ground for Hadid’s curiosity and creativity to flourish.

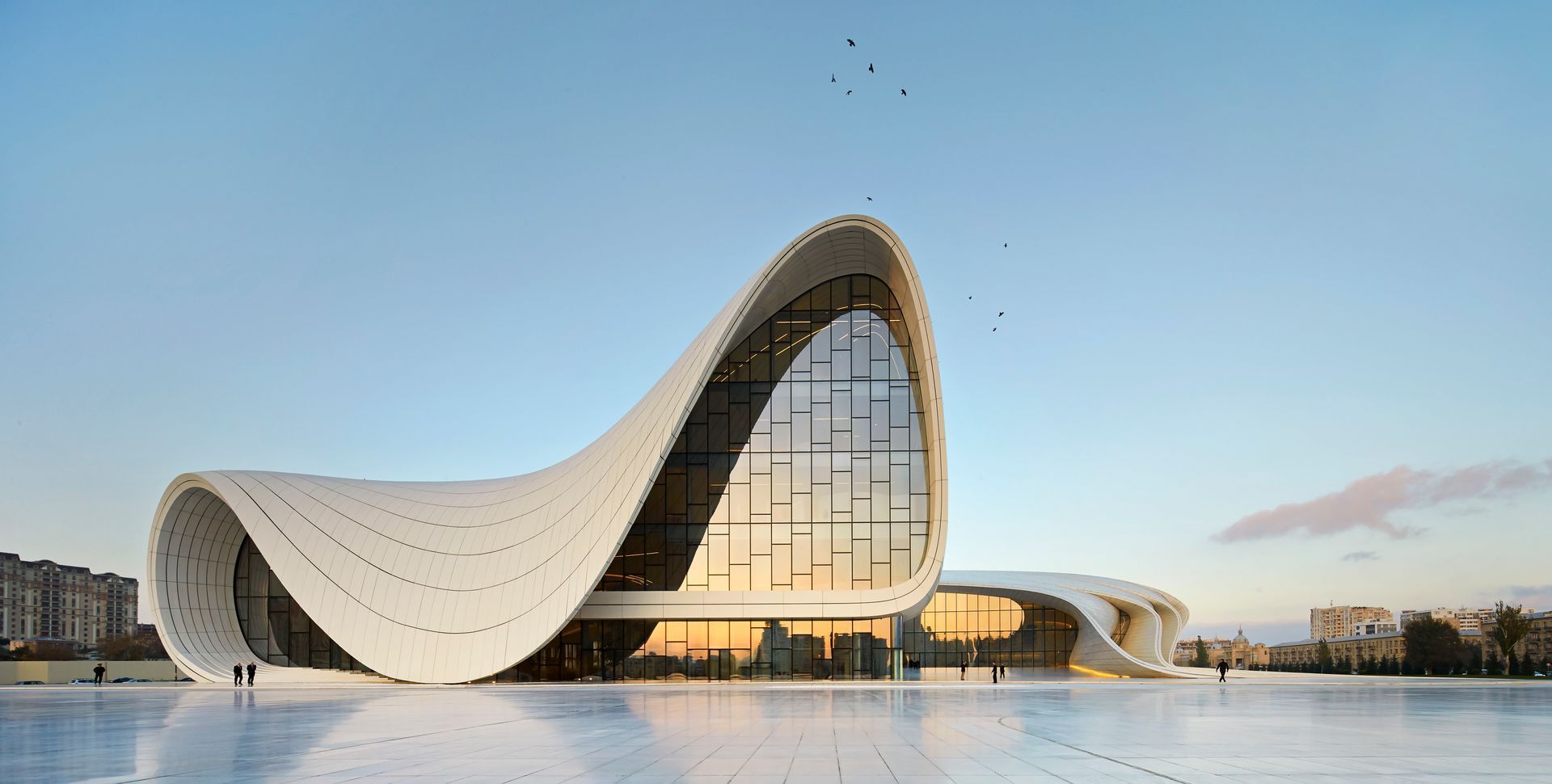

Heydar Aliyev Center in Azerbaijan

Hadid’s powerful architectural imagination saw her become a visioBEEAH Headquarters UAEnary – dubbed the ‘Queen of the Curve’ – who fundamentally altered the contours of modern architecture and design. She took inspiration from the rivers and the dunes of the Middle East. “There are 360 degrees. Why stick to one?” she famously said of her philosophy.

Across a career spanning decades, she pushed the limits of what can be created with concrete, steel and glass. From the Guangzhou Opera House in China to the Heydar Aliyev Center in Azerbaijan, and the MAXXI museum in Rome, Hadid’s daring designs defied gravity and convention, and blurred the boundaries between art, architecture and mathematics.

Hadid’s style was characterised by fluidity and dynamism, and her distinctive use of innovative materials and technologies. Her sculptural structures have become iconic destinations, drawing visitors from across the globe who seek to experience the awe-inspiring beauty she brought to life. Hadid also challenged traditional notions of who could be an architect: she was the first woman to break the glass ceiling of the “starchitect” universe, and the first woman to receive the Pritzker Prize for Architecture (considered the Nobel Prize of architecture) in her own right.

Reflecting on the architectural marvels of the 21st century, it is impossible to overlook the profound impact of Hadid, whose work left an indelible mark on the world and continues to inspire and influence new generations.

The foundations of greatness

Zaha Hadid was born on October 31, 1950, into a household that embraced both politics and the arts, and a city on the cusp of transformation.

Baghdad’s historic core, known as the Old City, featured labyrinthine streets, bustling markets, and stunning mosques and palaces that spoke to its illustrious past as the capital of the Abbasid Caliphate during the Islamic Golden Age. Landmarks such as the Al-Mustansiriya Madrasah and the Al-Kadhimiya Mosque were testaments to its historical significance. Elsewhere, though, the city was undergoing rapid urban change. Alongside them, new buildings influenced by international trends began to dot the cityscape. The styles ranged from neoclassical and Art Deco to mid-century modern designs, reflecting the cosmopolitan aspirations of the era.

Hadid’s early exposure to the contrasting architectural styles of Baghdad, and childhood travels with her father, are said to have influenced her artistic sensibilities and nurtured her passion for pushing the boundaries of design.

In the 1960s, Hadid attended boarding schools in England and Switzerland.

She excelled in mathematics and later studied the subject at the American University of Beirut. In 1972 she moved to London to study at the Architectural Association School of Architecture, where she honed her skills under the tutelage of influential mentors such as Rem Koolhaas and Elia Zenghelis. Hadid developed a unique perspective on the relationship between mathematical principles and architectural design; this fusion of disciplines would become a hallmark of her work.

When she graduated, Koolhaas described her as “a planet in her own orbit”. ‘We called her the inventor of the 89 degrees. Nothing was ever at 90 degrees. She had spectacular vision. All the buildings were exploding into tiny little pieces,” he said of her wildly imaginative designs.

Koolhaas recalled that she was less interested in details, such as staircases: “The way she drew a staircase you would smash your head against the ceiling, and the space was reducing and reducing, and you would end up in the upper corner of the ceiling. She couldn’t care about tiny details. Her mind was on the broader pictures—when it came to the joinery she knew we could fix that later. She was right.”

A ‘paper architect’

Hadid went on to work for Zenghelis and Koolhaas at their Office for Metropolitan Architecture in Rotterdam. Hadid became a naturalised citizen of the United Kingdom, and in 1979 set up her own firm – Zaha Hadid Architects (ZHA) – in London. A few years later she gained international recognition with her competition-winning entry for the Peak, a leisure and recreational centre in Hong Kong. Her design was a “horizontal skyscraper” that moved down the hillside site – but it was never realised in physical form.

Hadid became known as a ‘paper architect’ - her designs were too avant-garde to move beyond the sketch phase. Often executed as beautiful acrylic paintings, inspired by the works of the Russian suprematist artist Kazimir Malevich, they were instead exhibited in museums as works of art.

“They did not depict anything that could be conventionally identified as a building, but instead showed jagged landscapes in which walls and roofs, inside and outside, ground plan and cross section, merged seamlessly one into another. They were more like Piranesi dreamscapes than rational proposals for orthogonal buildings. But these were not abstractions or fantasies: they were the product of Hadid’s exploration of new ways to imagine how space might work,” wrote Deyan Sudjic in The Guardian in 2016.

Another ambitious but unbuilt project was Hadid’s plan for an opera house in Cardiff, Wales. In 1994 her design was chosen as the best by a competition jury, but the funding body refused to pay for it, and the commission was given to a less ambitious project. In response, Hadid asked: “Do they want nothing but mediocrity?”

Alongside her radical designs, Hadid earned her early reputation with her lecturing: she taught first at the Architectural Association, and would go on, over the years, to teach at Harvard Graduate School of Design, Cambridge University, the University of Chicago, the Hochschule für bildende Künste in Hamburg, the University of Illinois at Chicago, and Columbia University.

In 1988 she was among seven architects featured in the exhibition Deconstructivism in Architecture at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. The resulting press coverage helped get her name and unique style into the wider world. A few years later, her first major built design gave her the chance to – finally – shake off the notion that her buildings were unbuildable.

In 1993, Rolf Fehlbaum, the president-director general of the Swiss furniture firm Vitra, invited Hadid to design a small fire station for his factory in Weil am Rhein, Germany. (Fehlbaum had an incredible eye for design; in 1989 he had commissioned Frank Gehry, who was then a little-known talent, to build a design museum.) Hadid’s design was a sculptural work made of raw concrete and glass, resembling a bird in flight– and it provided a launching pad for a pioneering career. She is well known for some of her seminal built works, such as the Mind Zone at the Greenwich Millennium Dome (1999), a ski jump (2002) in Innsbruck, Austria, and the Rosenthal Center for Contemporary Art (2003) in Cincinnati, Ohio. The latter was the first American museum designed by a woman, and it solidified Hadid’s reputation as a formidable architect of built works.

“When people see something fantastic they think that it’s not possible to achieve it in real life,” she told The Guardian in 2013. “But that’s not true. You can achieve amazing things.”

Philosophy and style

At the heart of Hadid’s architectural philosophy was a desire to challenge conventions and reimagine the possibilities of space. Over the years, as new technologies and digital animation techniques rapidly developed, the sharp edges of Hadid’s early designs evolved into soft curves and waves. She reimagined the structural engineering of bold new forms, creating artistic expressions that blended form and function. Her buildings were more than structures: they became one with the natural topography of their environment, and provided an experience for those who visited them.

“I don’t think that architecture is only about shelter, is only about a very simple enclosure. It should be able to excite you, to calm you, to make you think,” she once said.

Hadid’s style is today characterised by the use of dynamic and organic forms. Her buildings appear to be in constant motion, with sweeping curves and undulating surfaces that defy traditional notions of rigidity. From the flowing lines of the Sheikh Zayed Bridge (1997-2010) to the sinuous curves of the Riverside Museum in Glasgow (2004-2011), her designs evoke a sense of movement and harmony, and embody the spirit of the 21st century, where technology and imagination intertwine.

Hadid did not view herself as a follower of any one style or school, but her work was often cited as an example of deconstructivism and neo-futurism. Hadid was one of the early adopters of a fully digitised 3D-design process, but she also continued to draw and paint her designs by hand, not wanting her creativity to brush up against the limits of a computer system. To describe her work, Hadid’s firm coined the term parametricism – an architectural style based on computer technology and algorithms.

“When we started, we already drew in a ‘parametric’ way, but by hand with a little help from the computer,” ZHA associate director Woody Yao told The Financial Review in 2019.

“All the 360-degree perspectives and so on were already very much a part of Zaha’s vision of buildings and objects. We were always about the pushing of boundaries, never about innovating for innovation’s sake.”

Groundbreaking projects

To truly grasp the magnitude of Hadid’s impact, one must look to some of her most notable and celebrated works.

The Heydar Aliyev Center in Baku, Azerbaijan (2014), with its sweeping curves and futuristic aesthetic, has become an architectural masterpiece. Hadid described its curves as allowing the structure to blur the boundaries between the architecture and the topography. The centre stands as a testament to Hadid’s ability to merge architecture and art, and create spaces that transcend their functional purpose. It won the London Design Museum’s Design of the Year award - the first time it was awarded to a woman, and the first time it was awarded for the architecture category.

In Rome, Hadid’s design for the MAXXI museum of the 21st century arts (2010) challenged traditional notions of museum architecture. The building’s fluid forms and interconnected spaces create a sense of exploration and discovery. It has redefined the museum experience, encouraging visitors to engage with art in new ways. It also earned Hadid the Royal Institute of British Architects Stirling Prize for the best building by a British architect completed in the past year. (She won a second Stirling Prize the following year for a structure she conceived for Evelyn Grace Academy, a secondary school in London.)

The Guangzhou Opera House (2010) represents the seamless integration of traditional Chinese architectural elements with Hadid’s futuristic design language. The building’s curvilinear forms and shimmering façade pay homage to the city’s rich cultural heritage while pushing the boundaries of architectural expression. It stands as a symbol of Guangzhou’s cultural renaissance and Hadid’s ability to create architectural icons.

Beyond these projects, Hadid’s portfolio boasts a diverse range of designs that showcase her versatility and creative prowess. From the breathtaking stingray design of the London Aquatics Centre (2011), to the dynamic Galaxy SOHO complex in Beijing (2012), each of her projects exhibits her ability to reimagine spaces and leave a lasting impression on the environment.

A trailblazer ‘on the edge’

When Hadid won the Pritzker Prize in 2004, the jury noted how consistently she defied convention. One juror said that even if she’d never built anything, Hadid would have radically expanded the possibilities of architecture.

Juror and architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable said: “From the earliest drawings and models to current buildings and work in progress, there has been a consistently original and strong personal vision that has changed the way we see and experience space. Hadid’s fragmented geometry and fluid mobility do more than create an abstract, dynamic beauty; this is a body of work that explores and expresses the world we live in.”

Hadid’s numerous other accolades included the Japan Art Association’s Praemium Imperiale prize for architecture in 2009, and the Royal Institute of British Architects’ Royal Gold Medal for Architecture – the world’s oldest and most established architecture prize – in 2016. In 2012 she was made a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire, the female equivalent of a knighthood.

Her influence stretches well beyond the awards bestowed on her. Hadid’s groundbreaking designs have inspired a new generation of architects to push the boundaries of what is possible; many have embraced her design principles, incorporating fluid forms, innovative materials, and parametric design into their own works. Her organic forms and sci-fi aesthetic have also found their way into product design, fashion, and even urban planning.

The versatile artist applied her creative touch on scales both large and small: she designed stadiums, schools, and factories, attracted acclaim for her furniture collection inspired by melting glacial ice, and collaborated with major fashion labels – from fashion spaces for Chanel and Stuart Weitzman to Adidas shoes, Louis Vuitton bags and Swarovski jewellery. She was even behind the stage set for the Pet Shop Boys’ world tour of 2009.

Bold, unapologetic, and progressive, Hadid carved a career in a field that had a longstanding reputation as a male-held profession, breaking stereotypes around what a woman – and a Muslim woman at that – could achieve. “I never use the issue about being a woman architect ... but if it helps younger people to know they can break through the glass ceiling, I don’t mind that,” she told Icon magazine.

She had high-profile industry friends – among them Norman Foster and Frank Gehry, who described her as “an extraordinary force of nature” – yet she admitted to feeling ostracised at times. She never compromised on her designs, had little patience, and was sometimes labelled a diva – a charge she rebuffed: “If I were a man they’d call me an opinionated maverick.”

“I’ve always been independent and because I’m ‘flamboyant’ I’ve always been seen as difficult,” she told The Financial Times in 2015.

“As a woman in architecture you’re always an outsider. It’s OK, I like being on the edge.”

BEEAH Headquarters UAE

Challenges and criticism

For all her success, Hadid was not immune from challenges and criticism.

Her fantastical designs were at times derided, and the expense and scale of her commissions often attracted criticism; a common complaint was that her structures were impractical, and ended up using 10 times as much steel than a simpler design would have. In a 2015 article, the Spectator UK summarised the disapproval: “Her fabulous forms were always eye-catching, but often difficult to build. And, almost always, so neglectful was she of tectonic practicalities that her buildings went deliriously over budget.”

The sheer amount of material in her design for the London Aquatics Centre sparked controversy, along with the $299 million pound cost, which tripled from the initial budget. “What do the critics know about how much steel should be in a roof?” Hadid said at the time. She was later forced to scale back her design.

Her design for a stadium for the 2020 Olympics in Tokyo (later postponed because of the coronavirus pandemic) was scrapped after mounting protests – notably from preeminent Japanese architects Arata Isozaki and Fumihiko Maki – erupted over her plan. Critics derided it as reminiscent of a bicycle helmet or drooping oyster and said it was out of sync with the neighbourhood. In an open letter, Isozaki declared it to be a “monumental mistake” that would “disgrace … future generations”.

More controversy followed after a 2014 report disclosed that some 1,000 foreign workers had died because of poor working conditions across construction sites in Qatar, where her Al Wakrah Stadium (later the Al Janoub Stadium) for the 2022 World Cup was set to break ground. When asked about the deaths, Hadid objected to her responsibility as an architect to ensure safe working conditions – remarks that were widely regarded as insensitive. An architecture critic exacerbated the situation when he falsely claimed that 1,000 had died building her stadium, though construction was yet to begin. Hadid filed a defamation lawsuit, and donated the undisclosed settlement sum to a charity protecting labour rights.

Her supporters felt that Hadid was subjected to controversies that her male counterparts were not. At all times, Hadid maintained an unwavering determination and commitment to her vision.

“Well, it’s not normal practice,” she once conceded. “We don’t deal with normative ideas and we don’t make nice little buildings. People think that the most appropriate building is a rectangle, because that’s typically the best way of using space. But is that to say that landscape is a waste of space? The world is not a rectangle. You don’t go into a park and say: ‘My God, we don’t have any corners.’”

An enduring legacy

On March 31, 2016, at the age of 65, Hadid died of a heart attack resulting from pneumonia. She had never married, and had no children, choosing to focus single-mindedly on her career. “I think about architecture all the time. That’s the problem. But I’ve always been like that. I dream it sometimes,” she said.

Hadid brought her dreams into reality, and opened our eyes to a new kind of architecture. Her architecture practice ZHA remains one of the world’s most inventive studios.

Zaha Hadid is often referred to as the greatest female architect of her time. Yet she never wanted to be characterised as a female architect, or even an Arab architect – she simply wanted to be known as an architect, and her work certainly stands up against that of celebrated male peers such as Frank Gehry, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Leoh Ming Pei.

It is perhaps impossible to say if she is the greatest architect of the 21st century – architecture, like all art forms, is subjective. But great art touches on the senses, and evokes emotion – and Hadid’s creations certainly achieved that. Her legacy is forever etched in our landscape, and her expressive, futuristic designs hold an enduring power to delight and astound those who encounter them.